When I first learned the basics of mosaic — things like the kind of glue to use to stick the tiles to paper, or the variety of ways to install a floor — little by little I was learning something else. These days I think of this thing as the most important thing I know. It sounds obvious, clichéd even, and in all likelihood you’ll feel it’s something you know already. All I can say is that it’s taken me a lifetime to understand its importance and I’m sure there are applications that I still haven’t grasped. The insight is this: if you are making some kind of visual work, you have to set up your own rules. It doesn’t really matter what rule it is — it could be that you break all possible rules, or that you always stick everything upside down, you simply have to do it consistently enough for us to understand the principle you are dealing with, and not so consistently that it becomes visually obvious and boring, unless boredom itself is the principle you are grappling with. So you make the rule, and then you can inventively break it, in such a way that we understand that you’ve broken it with intention.

I think this insight has probably made me a better teacher for some students than for others. There are plenty of people who will tell you what the rules are, and that is certainly a good place to start and develop. It’s good to know what material sticks to what so that the mosaic doesn’t fall to bits (unless disintegration is part of the point of your experiment.) But if you were to ask me about the rules of how to lay a mosaic — things that are asserted in books about mosaic — I’d have to say that there aren’t any, it’s just a matter of taste or tradition and those qualities can hamper as much as they help someone trying to make an something that looks interesting. On the other hand of course, it’s helpful to know and understand the framework and visual conventions of anything you put time and effort into. If you are cooking, it’s helpful to understand how and why you might want put ingredients together to produce the most intense and interesting flavours — likewise mosaic. It doesn’t hurt to know the conventions, if only in order to ignore them.

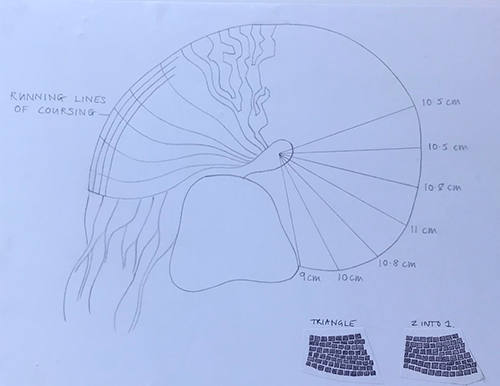

Yesterday, I talked about the convention of ‘two into one’ — making two lines of mosaic flow effortlessly into a single one, in a way that makes it had to see you’ve done it. There’s sure to be a Latin or an Italian name for this (like ‘chiaroscuro’ or ‘sfumato’ in painting) but being an English speaking self-taught mosaicist, I don’t use it. The point is that if you have a series of coursed lines of tiles of a similar size, ‘two into one’ causes the lines to diminish without lots of little triangles pointing like arrows and drawing the eye to something that may not be very important in the bigger scheme of your mosaic. (See images below). Of course, it’s worth remembering that you can use just this very principle — one of cutting triangles — precisely because you want someone to notice a particular area. In a mosaic mostly made of little squares, triangles stand out. It’s an effect that is sometimes overlooked. In the drawing of the nautilus shell below, you can see that the shell narrows at one end, and widens at the other. I’ve drawn a little insert to show you how you might deal with this, either by cutting triangles, or by making ‘two (lines flow) into one’.

The photo below shows an extreme example of how to flow the lines together. There are lots of examples in books of how to do this most effectively, but in fact there’s quite a lot of leeway, providing, once you’ve determined how you’re going to do it, you stick to the rule you’ve established. Or, as I said, break it in a way that gives us a sense of your intention.

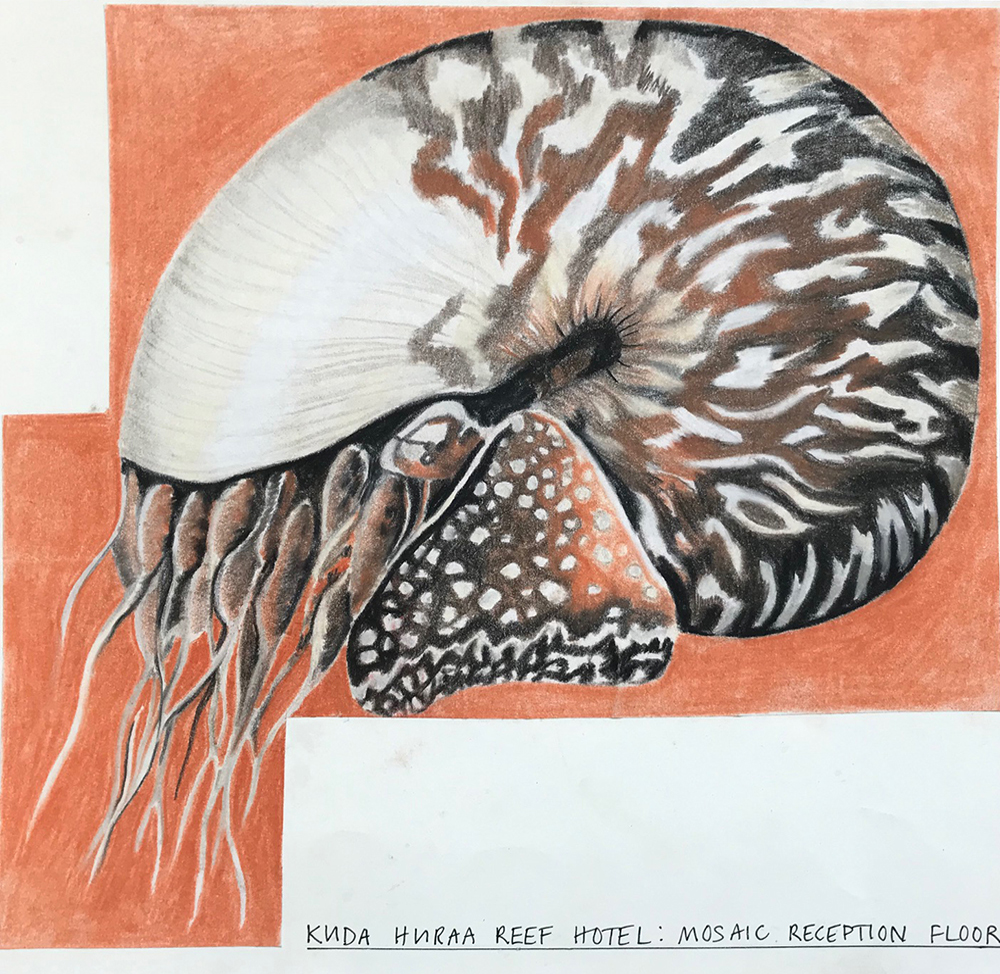

I’m sure I’ll come back to the ‘rule-no rule’ principle again, and carry on explaining it until it the ways in which it might be useful to you become clearer. But I want to point out that the photograph at the top of this blog is a preparatory drawing for the mosaic floor of a nautilus shell. If someone wants you to make a mosaic for them, they may well want to know what they are likely to get. In those days (I suppose it was about twenty five years ago) I used to draw with chalk pastels. These days I use crayons, or sometimes collage, for the freedom of interpretation it allows.